The Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam

Hi!! I hope you are all doing well!

Last week's blog post looked at some of the strategies implanted by the Nile Basin Initiative and the impacts they have had. For this week's blog, I am going to be looking at the hydro-politics at play with regards to the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam.

Background:

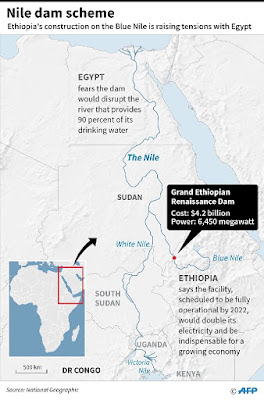

The Ethiopian Government revealed plans in 2011 to build a hydroelectric dam on the Blue Nile, lying approximately 45km away from Sudan's border (Hammond, 2013). The dam, named the Great Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) is the first hydroelectric dam to be constructed on the Blue Nile and is poised to become 'the largest hydroelectric power plant in Africa', being able to boast 'an annual production capacity of 6,000 megawatts' (Gebreluel, 2014: 25).

The Nile has been central to water politics within Africa over the past centuries, with Egypt having a monopoly over the river for a significant period of time, as pointed out within my previous blog posts. These water politics have become incredibly tense 'due to the pressures of population growth, industrialisation and climate change' (Gebreluel, 2014: 26). With population growth in Northeastern Africa 'set to double by 2050', combined with the implications of climate change, water scarcity will become even more prominent within the region (Gebreluel, 2014: 30). The construction of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam signifies Egypt's control over the Nile being challenged, who previously had been the 'dominant' user of the Nile (Whittington et al, 2014: 595). Whilst Ethiopia had claimed rights to the Nile in the past, it had not posed a threat to Egypt's control of the river until 2011 (Whittington et al, 2014: 595).

Benefits

Ethiopia has often been labelled as the 'Water-Tower of Africa' due to the fact that the country has an 'abundance of water resources' (Hammond, 2013). Ethiopia evidently has a 'significant hydro water potential' which has been untapped for a long period of time - in 2001, 'only 3% of its hydropower potential had been developed' (Hammond, 2013). Additionally, over 80% of Ethiopia's population do not have access to electricity - the consequent reliance on using 'biomass fuel' for day-to-day life is therefore a contributing factor towards the creation of health conditions and increased environmental pollution (Hammond, 2013).

The Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam has the potential to provide benefits to both Ethiopia and Egypt. For Ethiopia, the generation of hydropower will be a significant positive together with the possibility of selling any 'surpluses', as part of 'its regional economic integration scheme', to neighbouring countries (Gebreluel, 2014: 33). Egypt, on the other hand, will have access 'to a cheaper and more environmentally friendly electricity supply'. (Gebreluel, 2014: 33). In addition to this, the GERD has the potential to further benefit downstream countries, like Sudan and Egypt, by 'removing up to 86% of silt and sedimentation' (Tesfa, 2013).

Conflict

The construction of the GERD has faced significant opposal from Egypt, who have seen their 'historical hegemonic position be challenged' by Ethiopia (Hammond, 2013). In recent times, tensions have risen between Ethiopia, Egypt and Sudan, with the latter two countries being greatly dependent on the Nile for its water resources (Hammond, 2013). The construction of the GERD has provided a sense of concern for Egypt and Sudan, who believe that the dam would restrict the flow of the Nile and therefore be a threat towards their water resources (Guardian, 2019).

Politicians within Egypt have heavily advocated against the construction of the GERD, attempting to persuade the government to stop the dam coming to fruition (Gebreluel, 2014). In 2013, the former president of Egypt, President Morsi, received suggestions from politicians that 'Egypt should conduct a military attack on Ethiopia or sabotage it by funding armed rebels operating in its territories' (Gebreluel, 2014: 31). These suggestions came during a debate which was being shown on live television, with the politicians being completely unaware that they were being broadcasted. This all happened following Ethiopia's decision to start diverting the flow of the Nile, in preparation for the construction of the Grand Renaissance Dam (Gebreluel, 2014). Currently, the Aswan High Dam stands as the largest structure along the river, and has been 'a symbol of Egypt's hegemony on the river' (The Conversation, 2019). The construction of Ethiopia's dam therefore represents Egypt's hegemony and control over the Nile being challenged.

The Future...

Egypt continue to be dismissive regarding the potential benefits of the the GERD and still greatly oppose 'Ethiopia's right to develop its own water resources' (The Conversation, 2019). Egypt's opposal towards the building of the GERD can partly be attributed towards a lack of awareness with regards to the risks and benefits that the dam poses (Whittington et al, 2014). Going forwards, there is a win-win solution available that can benefit Ethiopia, Egypt and Sudan, but it requires the following conditions as quoted from Whittington et al (2014:595):

Last week's blog post looked at some of the strategies implanted by the Nile Basin Initiative and the impacts they have had. For this week's blog, I am going to be looking at the hydro-politics at play with regards to the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam.

Background:

The Ethiopian Government revealed plans in 2011 to build a hydroelectric dam on the Blue Nile, lying approximately 45km away from Sudan's border (Hammond, 2013). The dam, named the Great Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) is the first hydroelectric dam to be constructed on the Blue Nile and is poised to become 'the largest hydroelectric power plant in Africa', being able to boast 'an annual production capacity of 6,000 megawatts' (Gebreluel, 2014: 25).

The Nile has been central to water politics within Africa over the past centuries, with Egypt having a monopoly over the river for a significant period of time, as pointed out within my previous blog posts. These water politics have become incredibly tense 'due to the pressures of population growth, industrialisation and climate change' (Gebreluel, 2014: 26). With population growth in Northeastern Africa 'set to double by 2050', combined with the implications of climate change, water scarcity will become even more prominent within the region (Gebreluel, 2014: 30). The construction of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam signifies Egypt's control over the Nile being challenged, who previously had been the 'dominant' user of the Nile (Whittington et al, 2014: 595). Whilst Ethiopia had claimed rights to the Nile in the past, it had not posed a threat to Egypt's control of the river until 2011 (Whittington et al, 2014: 595).

Benefits

Ethiopia has often been labelled as the 'Water-Tower of Africa' due to the fact that the country has an 'abundance of water resources' (Hammond, 2013). Ethiopia evidently has a 'significant hydro water potential' which has been untapped for a long period of time - in 2001, 'only 3% of its hydropower potential had been developed' (Hammond, 2013). Additionally, over 80% of Ethiopia's population do not have access to electricity - the consequent reliance on using 'biomass fuel' for day-to-day life is therefore a contributing factor towards the creation of health conditions and increased environmental pollution (Hammond, 2013).

The Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam has the potential to provide benefits to both Ethiopia and Egypt. For Ethiopia, the generation of hydropower will be a significant positive together with the possibility of selling any 'surpluses', as part of 'its regional economic integration scheme', to neighbouring countries (Gebreluel, 2014: 33). Egypt, on the other hand, will have access 'to a cheaper and more environmentally friendly electricity supply'. (Gebreluel, 2014: 33). In addition to this, the GERD has the potential to further benefit downstream countries, like Sudan and Egypt, by 'removing up to 86% of silt and sedimentation' (Tesfa, 2013).

Conflict

|

| A map demonstrating the tensions between Egypt and Ethiopia (phys) |

The construction of the GERD has faced significant opposal from Egypt, who have seen their 'historical hegemonic position be challenged' by Ethiopia (Hammond, 2013). In recent times, tensions have risen between Ethiopia, Egypt and Sudan, with the latter two countries being greatly dependent on the Nile for its water resources (Hammond, 2013). The construction of the GERD has provided a sense of concern for Egypt and Sudan, who believe that the dam would restrict the flow of the Nile and therefore be a threat towards their water resources (Guardian, 2019).

Politicians within Egypt have heavily advocated against the construction of the GERD, attempting to persuade the government to stop the dam coming to fruition (Gebreluel, 2014). In 2013, the former president of Egypt, President Morsi, received suggestions from politicians that 'Egypt should conduct a military attack on Ethiopia or sabotage it by funding armed rebels operating in its territories' (Gebreluel, 2014: 31). These suggestions came during a debate which was being shown on live television, with the politicians being completely unaware that they were being broadcasted. This all happened following Ethiopia's decision to start diverting the flow of the Nile, in preparation for the construction of the Grand Renaissance Dam (Gebreluel, 2014). Currently, the Aswan High Dam stands as the largest structure along the river, and has been 'a symbol of Egypt's hegemony on the river' (The Conversation, 2019). The construction of Ethiopia's dam therefore represents Egypt's hegemony and control over the Nile being challenged.

The Future...

Egypt continue to be dismissive regarding the potential benefits of the the GERD and still greatly oppose 'Ethiopia's right to develop its own water resources' (The Conversation, 2019). Egypt's opposal towards the building of the GERD can partly be attributed towards a lack of awareness with regards to the risks and benefits that the dam poses (Whittington et al, 2014). Going forwards, there is a win-win solution available that can benefit Ethiopia, Egypt and Sudan, but it requires the following conditions as quoted from Whittington et al (2014:595):

- 'Ethiopia needs to agree with Egypt and Sudan on rules for filling the Grand Renaissance Dam reservoir and on operating rules during periods of drought

- Egypt needs to acknowledge that Ethiopia has a right to develop its water resources infrastructure for the benefit of its people based on the principle of equitable use'

Until Egypt recognises that the GERD has the opportunity to provide positive connotations for both Ethiopia and Egypt, the possibility for conflict between these countries will always be present.

Comments

Post a Comment